The Type 35 is the car that gave Bugatti its blueprint, one that combines unmatched performance with uncompromising luxury, making the Molsheim manufacturer like no other in annals of the automotive history. This beautifully proportioned eight-cylinder machine was the very embodiment of form-defining function.

The Type 35’s silhouette is instantly recognisable – a graceful yet assertive form that balances aesthetic elegance with aggressive sporting intent. Its bodywork, characterised by flowing lines and a distinctive radiator grille, exudes a sense of motion even at a standstill. This distinguished aesthetic was part of a clearly defined function. The Type 35 was a true thoroughbred race car.

Designed and engineered under the leadership of Ettore Bugatti, the car featured a series of world-firsts to deliver exceptional agility and performance. In a career spanning more than 10 years, it would claim over 2,500 victories and podium finishes.

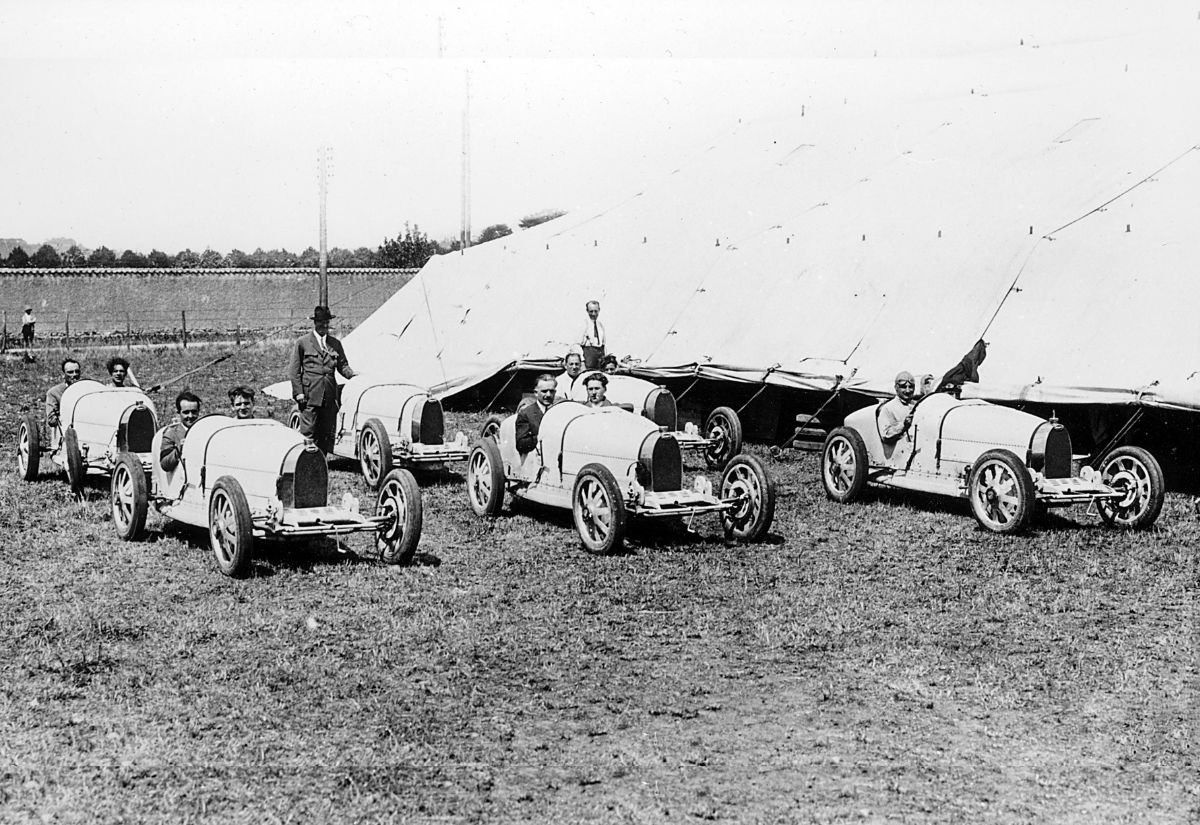

Despite these inherent qualities, the car which would go on to become the marque’s most successful racing car of all time, both on the race track and in the salerooms, did not get off to the best start when it made its debut at the 1924 Grand Prix at Lyon-Givors. On the contrary, its competition debut was fraught with challenges.

Five Type 35 were entered in the 1924 Grand Prix at Lyon, a race held by the Automobile Club de France over 35 laps of a 23.1 km road circuit. A sixth – the original prototype – was kept in reserve. The cars were driven from Molsheim to Lyon without encountering any problem.

During practice stone guards in front of the radiator and a cowl in front of the driver were fitted along with a thermometer in the radiator cap, but no issues or concerns were raised. And so, once the race was underway, drivers Jean Chassagne, Pierre de Vizcaya, Leonico Garnier, Ernest Friderich and Bartolomeo “Meo” Costantini could not have foreseen the difficulties they’d face.

But it wasn’t the car itself which had the first issue on track. The special tyres made for the Type 35 would prove troublesome, with the first failure occurring on the very first lap, on de Vizcaya’s car. Worse was to come for him on the third lap, when a tread separated from the sidewall, setting a precedent for the drama that would unfold in front of the 100,000 spectators lining the route.

Further failures occurred, sometimes combined with sheer bad luck. Sections of tread which had come away from Chassagne’s tyres became entangled in the steering, while Costantini – who also had cooling problems because of leaks from a soldered joint in the radiator overflow pipe – suffered the misfortune of a piece of tread wrapping around the gear lever.

This bent the gear lever and, as a result, Costantini couldn’t select 2nd or 4th gear. This in turn resulted in damage to the gearbox and ultimately the car’s retirement from the race. He was rewarded with the fastest lap at least, demonstrating not only his skill but also the Type 35’s inherent qualities.

But more bad luck lay in store for the Bugatti team. Several other drivers had to retire as the race progressed, with Chassagne, the highest-placed of them, finishing in seventh.

Investigations after the race revealed the tyre problems were caused by manufacturing defects. They had not been vulcanized properly – the process in which they are heated to give the finished tyre its desired properties. As a result, they could not withstand the stresses imparted by racing. However, these failures adequately demonstrated the strength of Type 35’s innovative lightweight cast aluminium wheels.

Reporting on ‘Lessons of the Grand Prix’, following the Lyon race, The Motor observed that: “Contrary to expectations, these not only stood the race, but showed no signs of the terrific battering which they must have received through a large amount of running on the rim, caused by the bursting of the tires.”

Following a change of specification and supplier, Ettore Bugatti wrote in a letter that he’d driven 520 km from Strasbourg to Paris in a Type 35 fitted with the new tyres – at an average speed of nearly 100 kmph. Convinced of the car’s fundamental integrity, he went on to state: “Ten of these cars have been built. They are almost all sold to customers. Some are already delivered and are a joy to their owners. One can use them as easily in town as in any race. I hope on the next occasion to make a better demonstration of the quality of my construction.”

That opportunity came at the Grand Prix in San Sebastian. This proved a much more successful outing, with Costantini once again setting the fastest lap, and going on to second place. With the teething troubles behind it, the Type 35 quickly evolved into an unrivalled race winner.

Success on the circuit was just part of the iconic car’s achievement. It was commercially successful as well, enabling Bugatti to sell the Type 35 to customers after race-winning weekends. As its legend grew, it was further improved through a series of enhancements making it more powerful, more agile, and even more competitive as the years passed.

Ettore Bugatti, the visionary behind this masterpiece, set out with a clear objective: to create a vehicle that would dominate the racing world while simultaneously capturing the imagination of those who appreciate the finer things in life. With its debut in the mid-1920s, the Type 35 did just that, redefining what was possible in automotive design and performance.